| And it will be, when you come to the land that G-d your G-d is giving you as an inheritance, and you possess it and settle in it, | Ve-haya ki tavo el ha-aretz asher adoshem elokecha noten lecha nachala, vitisha vayashavta ba, | וְהָיָה כִּי־תָבוֹא אֶל־הָאָרֶץ אֲשֶׁר ה’ אֱ-לֹהיךָ נֹתֵן לְךָ נַחֲלָה וִירִשְׁתָּהּ וְיָשַׁבְתָּ בָּהּ׃ |

Torah Thoughts

Ki Tavo begins with the recitation to be said by one bringing the first fruits of the harvest to the Temple. The words will be familiar; they are exactly what we recite on Passover every year.

One did not simply come to the Temple and say with pride “look what I brought!”

Read the beginning of the parsha. One must come to the Temple, and remember: For every one of us knows: “My father was a wandering Aramean.” And he went to Egypt with a small group of descendants, but grew numerous. And the Egyptians dealt harshly with us. And G-d heard our cries, and took us out, sustained us through 40 years in the desert, and brought us here, and gave us this land. And THAT is why we are able to give the fruit.

At every moment, and particularly on joyous occasions, every Jew must remember whence we came, and the source of the blessings we have had.

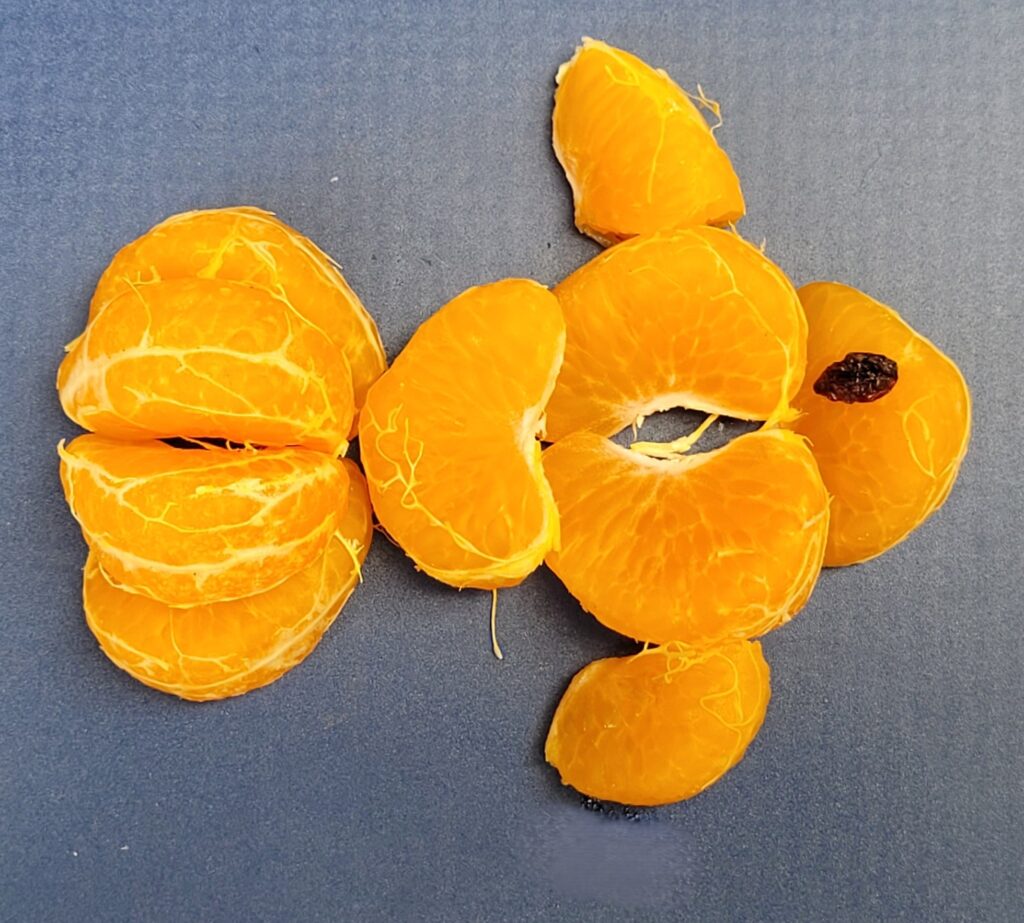

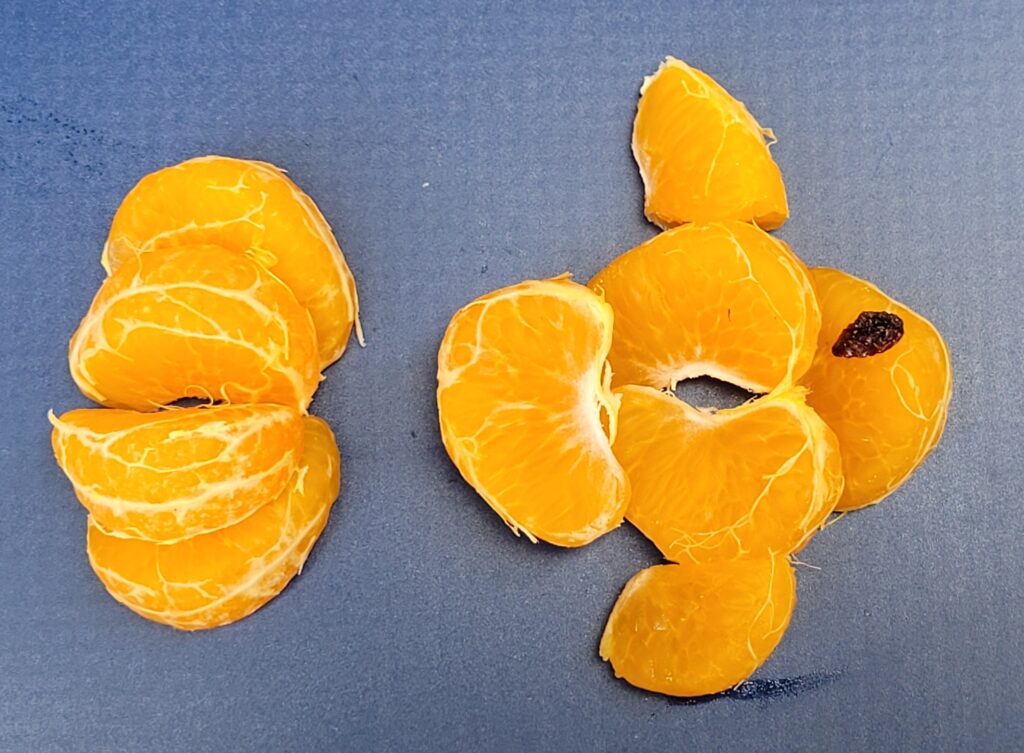

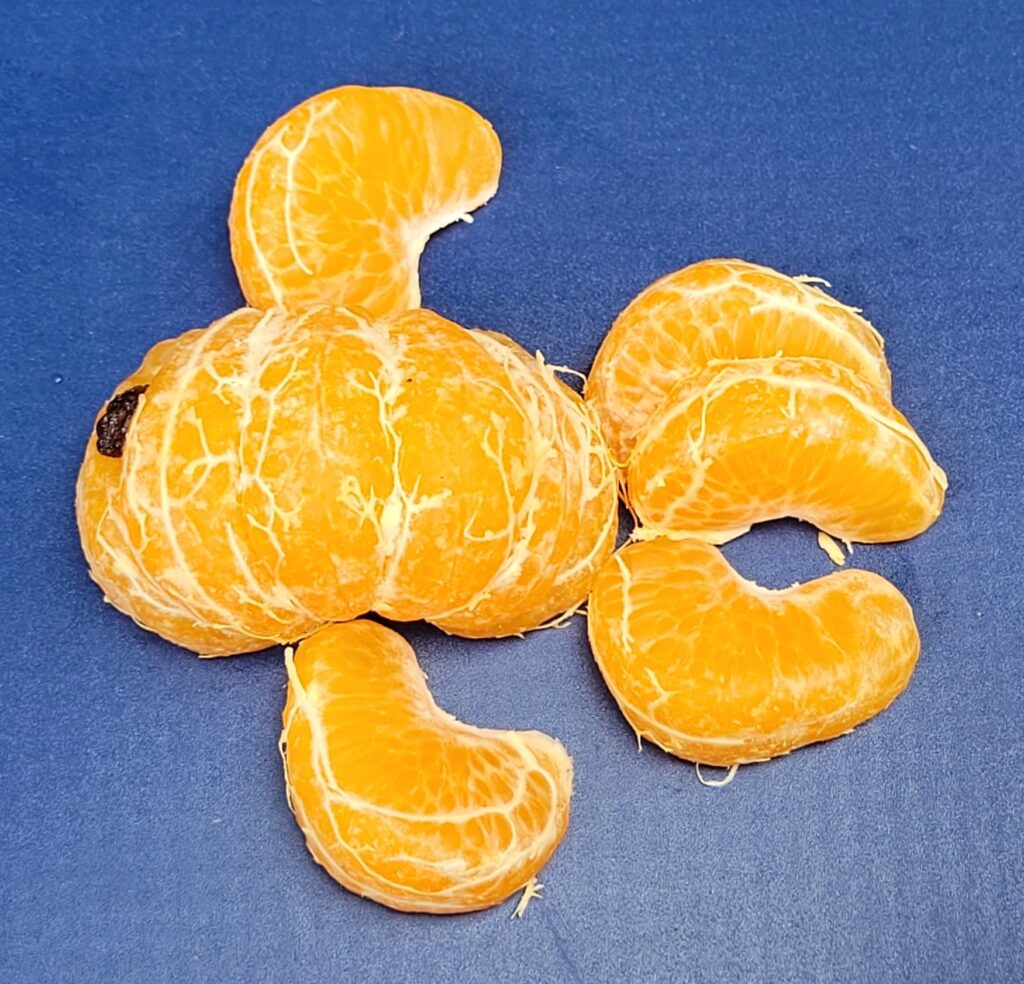

Judaism is a practice in mindfulness. We acknowledge and are grateful for waking up in the morning, for the fact that our bodies function, for rainbows, for rain, for food, for being satiated, for the fact that the sun rises and sets each morning, for the months that follow one another, and for the seasons that come when they should. This way, we do not end our lives saying “I wish I had appreciated what I had.” If we are paying attention to the words we say, we make sure we do.